I recently led a cartooning workshop at STAMMAFest, a stuttering conference organised by STAMMA, a United Kingdom-based charity and membership organisation representing people who stutter. It was the first time I gave my new workshop based around teaching participants how to draw a cartoon character of their stutter. I had done the same thing with my own stutter for my side hustle, FrankyBanky.com, dedicated to stuttering awareness and empowerment.

I am not exaggerating when I say the results of my workshop were life-changing. Many participants shared with me that the activity changed their negative perspective towards their stutter into a positive one. Like having a companion join them on their journey through the ups and downs.

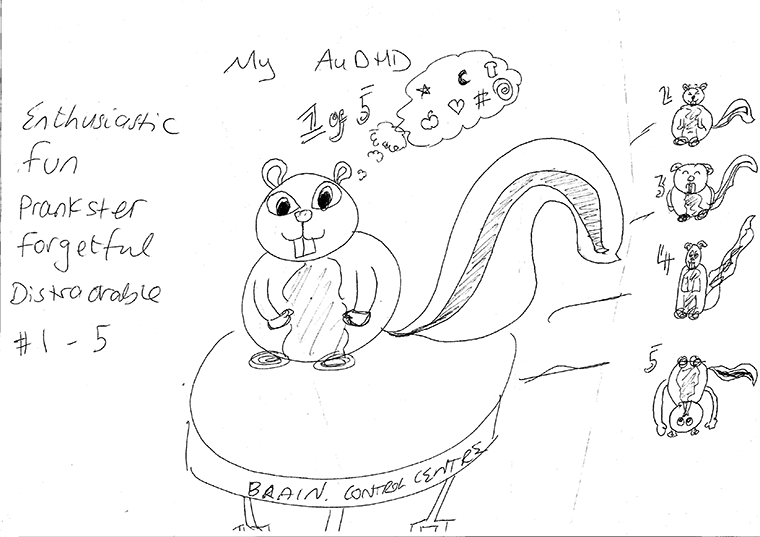

In the audience was my friend, Penny, who doesn’t stutter so she drew a cartoon character of her AuDHD, which is the experience of being both autistic and having attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). She shared that it helped her explain her experiences to the people sitting at her table – it clarified and destigmatised her own thoughts and attitudes as she talked through her character.

Penny drew her character as five different squirrels. Each with their own personality and focus of attention. They shift at random times into taking the “brain control” position. This illustrates Penny’s experiences in having fluctuating levels of attention, interest, and planning skills. She never knows which squirrel is at the helm or how long they’ll stay.

Along with the workshops I’ve given where I taught participants how to draw comics based on their speaking experiences with stuttering over the years, I’ve also learned that drawing can help people:

- think through their experiences and feelings;

- communicate internal emotions of their struggles;

- explain what it’s like to live with their disability(ies).

What does this have to do with user experience design?

This made me wonder if cartooning can be applied to user experience design. And I think it can!

Cartooning, in general, enables people to express their feelings and emotions about whatever they are experiencing. Be it a trip to a new country, living in a conflict area, or getting through a season of life. This also includes interactions with technology, products, and most importantly for people with disabilities – accessibility barriers, rather than just what they do.

Cartooning has the power for UX designers to go beyond the standard data-driven format at the user research and persona creation stages and add an emotional layer. Especially for users with disabilities.

After witnessing what happened at my workshop, I’m safely assuming that when people draw their disabilities beyond stuttering and AuDHD, as cartoon characters, they are externalizing their internal experiences in a way that might be difficult to convey through words alone.

Meanwhile, comics are a medium that fully immerses readers into the character’s environment, struggles, and frustrations (read: barriers) as they use your product or live their daily lives.

Imagine the deep, richer insights cartooning can provide for UX design teams that traditional user interviews might miss. User personas will be enriched from emotional and personal stories and thus, leading to more empathetic and well-rounded product design. And, most importantly, products that are accessible are often easier for users of all abilities to interact with – something organizations often need reminding.

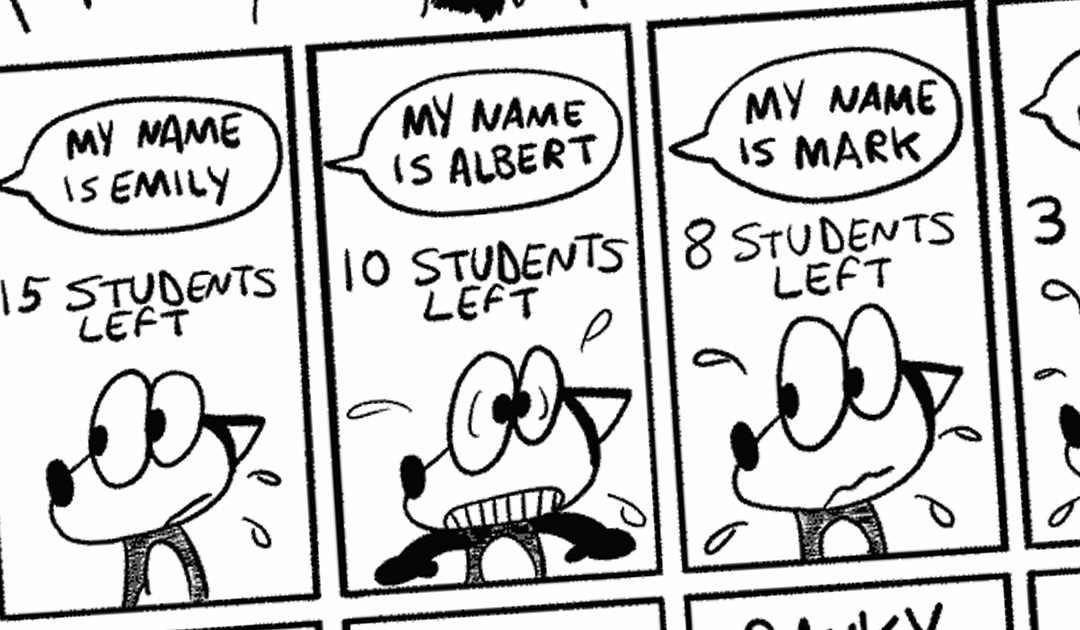

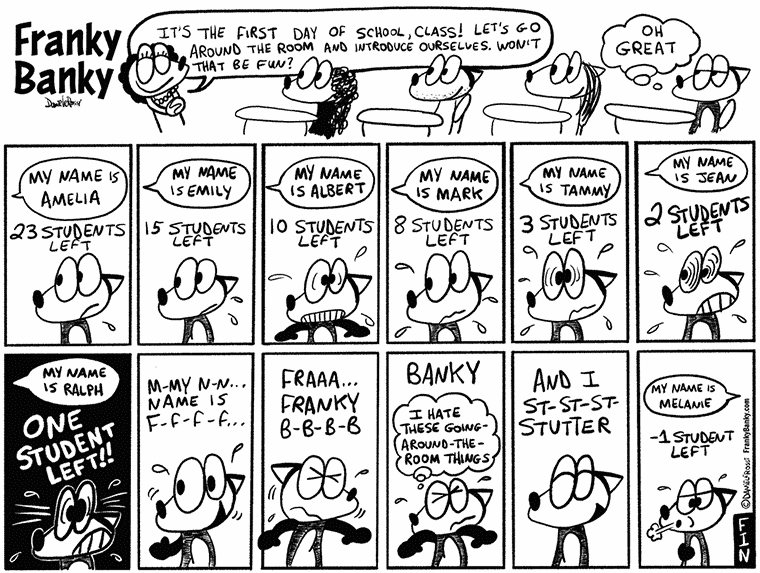

This is a comic strip I drew for my aforementioned side hustle. I use humour to explain a common icebreaker activity on the first day of school that causes a lot of anxiety for students who stutter – having each student in the classroom take turns saying their names. People who stutter often have a hard time saying their own name.

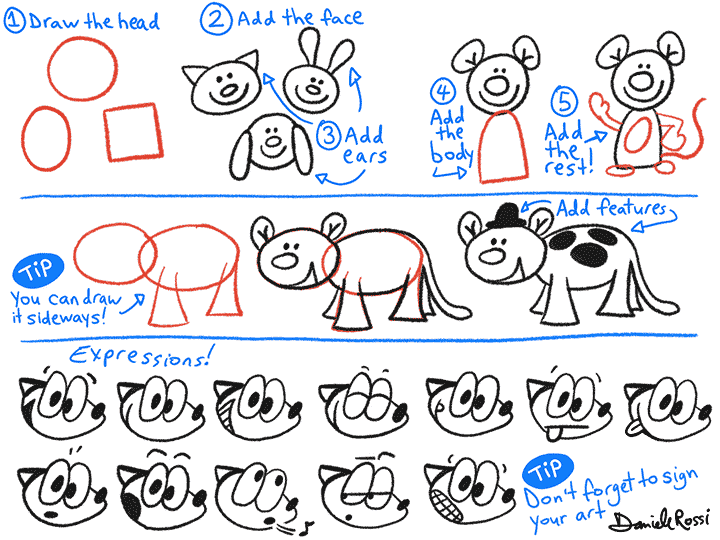

A polished Marvel or Disney style art is not the intended outcome for the activity.

This is about learning participants’ emotions, frustrations, and barriers. Fortunately, drawing stick figures are equally effective at storytelling. Just like the award-winning KXCD comics. So perfect illustration is not mandatory.

For example, I was able to teach participants how to draw stick figures in under a minute through a simple demonstration at STAMMAFest. I also provided an at-a-glance cheat sheet on a slide showing how to draw different kinds of heads, bodies, and facial expressions.

Inclusive options for drawing

You can offer multiple ways for participants to express their ideas so they aren’t restricted by their physical abilities. For example:

- People with limited mobility can participate by using assistive or adaptive technology.

- People with low vision can work with a facilitator who sketches their thoughts and emotions as they share their story.

- Pre-made character templates can help participants create visual representations quickly, especially over video chats with whiteboards.

Scaled-down versions of the exercises can also be an option due to budget and time considerations.

In conclusion, adding a cartooning aspect to traditional structured, data-driven user research methods can provide a more holistic view for UX designers. Bringing in personal stories in a visual way will make user personas more relatable, and thus, leading to more thoughtful and user-friendly designs. Especially for people with disabilities. And as I have mentioned earlier, the more accessible a product, the easier it is for everyone to use.